By: Frederick Kremkau, PhD

There are two fundamentally different operating principles present in the sonographic systems commercially available currently. Therefore, a new approach to teaching and testing sonographic principles is necessary. For over 50 years, one principle has been operating. Now there are two, providing dramatically different results. Students must be prepared to encounter both when they graduate.

The fundamental pulse-echo principle that has been in use in conventional sonography for decades states that a pulse of ultrasound is sent into the anatomy to be imaged and the returning echo stream is displayed as a visible scan line. This is repeated about 100 to 250 times to form one frame of the anatomic image. In conventional sonography there is a one-to-one correspondence between the emitted pulse and the returning echo stream that appears as a scan line on the display (ignoring the detail that, in some cases, multiple scan lines can be presented from one emitted pulse, typically two or four). The best detail resolution occurs in the focal region of the focused, transmitted beam. A laser-thin beam would produce excellent detail resolution everywhere in the image. Unfortunately, the high frequencies necessary to produce such a beam would not allow the penetration necessary for human anatomic imaging. Conversely, a broad, unfocused beam would produce a useless image with unacceptable detail resolution throughout.

Newer, more sophisticated sonographic instruments operate on an entirely different principle, termed virtual-beam sonography. In this approach, a few broad, unfocused pulses are emitted to acquire the echo information and massive, retrospective, computational beam-forming is accomplished with graphic processing units (GPU’s). Conceptually, this processing determines the echo received from each pixel location. The challenge in this is that echoes from multiple locations arrive simultaneously at the transducer elements (see Figure 1). This mixed-up result must be sorted out to determine each echo amplitude (and Doppler shift if desired) with its correct location on the image. GPU’s can do this sorting so fast that it can be accomplished at higher frame rates than conventional sonography. Virtual beam-forming provides improved detail resolution (i.e., the entire image is in focus; see Figure 2), contrast resolution and temporal resolution (fewer pulses are required to acquire all the echo information for an image; frame rates can be in the 100’s), increased sensitivity and penetration, artifact reduction and improved Doppler operation (simultaneous gray-scale, color and spectral Doppler implemented; see Figure 3 and Reference 1). See References 2 and 3 for further explanation of how virtual beam-forming is accomplished and other examples of its impact on imaging.

Figure 1. Each rain drop produces a circular, out-going wave. Multiple waves arrive at the edges of the photograph simultaneously in a combined form similar to ultrasound waves arriving simultaneously at transducer elements from multiple locations in the anatomy and therefore, in the image.

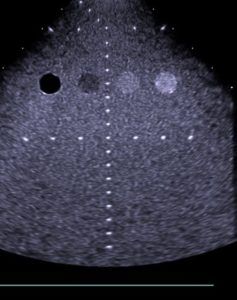

Figure 2.A Figure 2.B

Figure 2. A, Scan of a phantom showing the entire image is in focus.

B, Twin pregnancy showing excellent detail and contrast resolution.

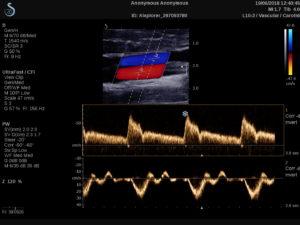

Figure 3.A Figure 3.B

Figure 3. A, Retrospective sample volumes and spectral displays are available from anywhere in the color box after the patient has departed.

Note frame rate of 156 Hz!

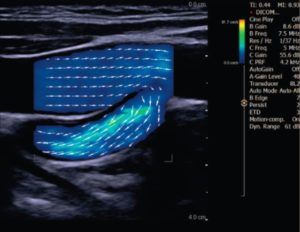

B, Vector flow shows arrows indicating flow direction and speed at any location in the color box.

The color map is calibrated in cm/s of flow speed, not kHz of Doppler shift.

Educators must begin to incorporate this virtual beam-forming into their curricula. Eventually, it will be included in the JRC-DMS National Education Curriculum and the SPI examination content.

References

- Kremkau FW: The new paradigm for understanding, teaching, and testing sonographic principles. J Vasc Ultrasound 2018;42(4):198–202.

- Kremkau FW: Your new paradigm for understanding and applying sonographic principles. J Diag Med Sonog 2019;35(5):439-446.

- Kremkau FW: Sonography Principles and Instruments, ed. 10, Chapter 6. Saunders/Elsevier, January 2020.

About the Author

Dr. Kremkau is Emeritus Professor of Radiologic Sciences at Wake Forest University School of Medicine and is a Past President of the AIUM.

The content, information, opinions, and viewpoints expressed in this article are those of the author. ARDMS makes no warranty, expressed or implied, as to the completeness or accuracy of the content contained in this article and ARDMS shall not be responsible for any errors, omissions, or inaccuracies in these materials, whether arising through negligence, oversight, or otherwise. ARDMS cannot be held responsible for your use of the information contained in this article.